Dear visitor

You tried to access but this page is only available for

You tried to access but this page is only available for

Witold Bahrke

Senior Macro and Allocation Strategist

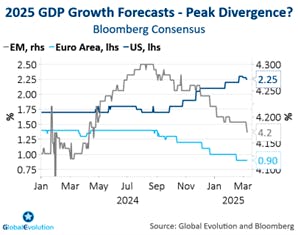

One of the dominant macro trends over the last two years was the remarkable outperformance of the US economy vis-a-vis the rest of the world, commonly known as US exceptionalism. Not only has US growth stayed around its trend despite headwinds from rising rates and Dollar strength. The US also outperformed most other regions. Emerging Markets were no exception as the gap between EM and DM growth narrowed in 2023 and 2024 (see chart below).

US exceptionalism has arguably been the decisive macro factor driving the relative performance of the main EM fixed income segments in 2024. 2025 will be no different, in our view. Last year, the relative strength of the US economy sent the Dollar from strength. The flipside of the coin was EM currency weakness. Consequently, local currency EM debt was the big underperformer within EM debt with negative returns in 2024, driven by EM currency depreciation.

A key question for 2025 therefore is whether the US economy will continue to outperform other regions and EM growth, in particular. That’s overwhelmingly the view among economists. For months, US growth expectations have been revised higher, while other regions saw their growth estimates being lowered (chart below). Apparently, Trump’s “make-America-great-again” agenda turned forecasting growth for this year into an extrapolation exercise.

However, extrapolating US exceptionalism seems all too rational to us. On the contrary, we think the macroeconomic balance of power should shift towards the rest of the world in 2025. Why do we believe US exceptionalism has passed its peak? Three factors stand out: The US is about to lose its fiscal edge versus the rest of the world, Trump 2.0 might be less great for America than meets the eye and the growth boost from immigration into the US is fading.

Shifting fiscal fortunes

The US economy is losing its fiscal oomph. In contrast to the past two years, fiscal policy should be a headwind to US growth over the coming quarters. Outside of the US, the opposite is the most likely scenario.

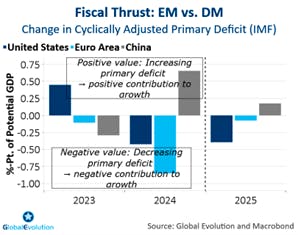

Near-term, Washington’s ambition to reduce public spending and difficulties in delivering tax cuts beyond an extension of expiring tax reductions from the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) translates into fiscal headwinds in 2025. Hence, the change in the cyclically adjusted fiscal deficit – a proxy for how fiscal policy impacts GDP growth - is likely to decline (see chart below). This would fit well with recent rhetoric from White House staff, expressing a desire to lower the long end of the US interest rate curve, partially through government spending cuts. The bond market seems to be the new success barometer for Trump. The upshot is that significant fiscal stimulus is unlikely. To be sure, the era of fiscal excess in the US is not over. Overall deficits are likely to remain around 6% of GDP. However, the contribution from fiscal policy to GDP growth is about the change in the deficit and should therefore be lower in 2025 and 2026 as compared to the previous two years.

This stands in contrast to the fiscal prospects outside the US. On the other side of the pond, an urgent need to ramp up military spending is felt. The new US government is questioning US security support for Europe, calling for a sizeable increase in defense spending in other NATO member states. The US wake-up call has been heard loud and clear in EU capitals. It's early days and details are scant, but the EU commission has recently proposed a combination of softening the EU fiscal rules and a common funding vehicle, which could increase defense spending by more than 1 %-pt. of GDP. An increase from currently around 2% of GDP in defense spending to 3% therefore looks realistic, especially if the German proposal to up military and defense spending is ratified (see below). Debt-financed defense spending tends to have a higher fiscal multiplier than budget-financed spending and could feed into GDP growth almost one-to-one. So even a gradual increase should leave its mark on European GDP growth.

Germany could be a prime example of a nothing short of a fiscal regime shift in Europe. Chancellor-in-waiting Merz and his most likely coalition partner in the new government (SPD) have proposed a ginormous 500bn EUR infrastructure package (over 10 years) as well as exempting defense spending above 1% of GDP from the debt brake rule. Effectively, this allows for open-ended spending on defense, marking another “whatever-it-takes” moment in Europe. The plan is to circumvent the potential obstacles to amend the debt-brake rule in the new parliament, where the opposition has a blocking minority, by fast-tracking it through the old parliament within the coming weeks. A third party (the Greens) needs to get on board to obtain the required 2/3 majority to change the constitution. This appears to be a relatively low hurdle to clear. As a consequence, defense spending could already rise to 3% of GDP within a year. Finally, it is important to highlight that even without the assumption of additional defense and infrastructure spending, headwinds from fiscal policy on growth should all but fade in 2025 (chart below).

China’s fiscal potential is likely to contribute to a more balanced fiscal picture, as well. The structural deficit expanded last year already. Still, China has kept much of its powder dry, awaiting more clarity around US trade policy in order to be able to respond adequately. As an important signal, on this year’s National People’s Congress, Beijing raised the deficit target from 3% to 4% of GDP for 2025 and declared boosting private consumption to be its first priority, up from a third place last year. Once the White House publishes its report on trade practices on April 2, we expect China to release additional fiscal stimulus with a particular focus on supporting households. Therefore, China’s fiscal impulse has the potential to surprise to the upside relative to what’s baked into the IMF’s forecasts (see chart below).

Trumponomics: Overlooked two-way risks

At a first glance, Trump’s “make-America-great-again” agenda is at odds with peak US exceptionalism.

However, important aspects of Trump 2.0 actually reduce future US economic outperformance while spurring growth elsewhere. These “unintended” effects could become the dominating factors in 2025. Recent US data releases point in this direction, highlighting the downside risks to US growth stemming from the confidence channel. After an initial post-election “Trumphoria”, the mood among corporates and consumers is souring, illustrating the two-way risks to growth from Trumponomics. Tariff risks are top-of-mind according to surveys, lifting inflation expectations and denting US household’s view on future prospects (chart below).

Geopolitical uncertainty is the enemy of growth and we have seen this movie before. During the initial bout of trade restrictions under Trump’s first term, US manufacturing was in decline compared to the rest of the world. At that time, the US’ effective tariff rate doubled between 2017 and 2020.

At the same time, geopolitics might actually have a positive impact on growth outside the US, albeit clearly not via trade. First, Trump’s intention to reduce miliary support to other countries (first and foremost NATO members) lifts the incentive to spend more on defense elsewhere. Secondly, US exceptionalism is to some extent a self-moderating force, as the resulting appreciation of the trade-weighted Dollar has improved the competitiveness outside the US, which should cushion the blow from higher US tariffs.

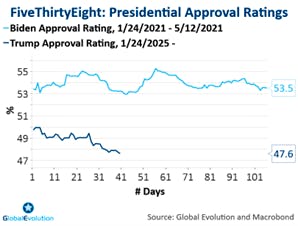

To be clear, geopolitics factors remain a source of market volatility going forward. But medium-term, bad news might be good news, supporting our “bark-is-worse than-the-bite” thesis when it comes to Trump 2.0. Trump’s approval ratings have declined recently and are somewhat below Bidens approval ratings after inauguration. The message from US voters is clear: Less policy uncertainty is required to keep the US on a solid growth path. Eventually, Trump will listen.

US Immigration: Exceptional no more

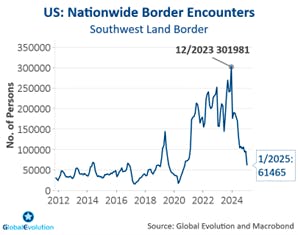

Trump 2.0 isn’t all about trade policy and defense. The US administrations clamp down on immigration, particularly via the Mexican border, creates additional downside risk to growth and keeps inflation risks elevated. Since 2000, around 1.5m immigrants entered the US per year according to calculations from the Congressional Budget Office. In 2023 and 2024, that number doubled. From a supply side perspective, the estimated lift to potential GDP ranges between ½-1 %-pt. The demand side impact is difficult to gauge, but judged by stubbornly high job growth, it had a significant impact, as well.

But things are changing fast. As the below chart illustrates, immigration has already been slowing markedly in the last months of the Biden administration. Given Trump’s ambition to restrict immigration and even engage in deportations, it is not a particularly brave prophecy to say that the inflow of immigrant will slow further, affecting labour supply negatively, as well.

The inflow of potential workforce has been a key factor behind the US ability to stage a soft landing last year. By boosting labour supply, it not only supported growth, but also helped keeping wage growth in check. The deterioration of the trade-off between growth and inflation in the US would have been even worse without the immigration boost.

Peak US exceptionalism – what does it mean for EM?

In our opinion, we see two important takeaways for EM debt investors. Firstly, peak US exceptionalism results in a more balanced global growth picture in 2025 and beyond. It is our belief the growth gap between the US and EM countries may widen in EM’s favour, reversing the 2023-24 trend (see first chart). Provided the US business cycles bends, but doesn’t break, such improved EM macro performance should be reflected in EMD returns, as well. Secondly, it allows monetary conditions to ease.

Less US-heavy global growth takes wind out of the Dollar’s sails. Given its reserve currency status, the greenback is a key contributor to global monetary conditions. In addition, a weaker US growth picture due to fading “Trumphoria” would allow the Fed to cut rates further, albeit only moderately so as inflation uncertainty remains elevated. Both factors contribute to easier monetary conditions as compared to 2024.

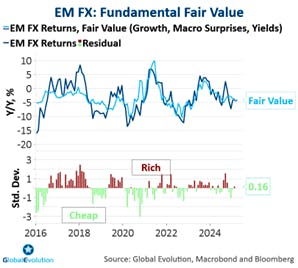

Which segment benefits the most from peak US exceptionalism? Somewhat against the current consensus view, local currency EM sovereign debt stands out to us. This segment is expected to outperform hard currency EM sovereign debt in the coming quarters as it is the most direct beneficiary of fading Dollar strength. Being the main victim of US exceptionalism in 2024, EM currencies are as cheap as they were in Q4 2022 (see chart below). Such attractive valuations tend to lay the groundwork for solid performance in the subsequent quarters – especially if the macro backdrop becomes more favourable for EM.

Markets have begun to smell the cracks in the US exceptionalism theme. Year-to-date, local currency EM sovereign bonds have outperformed their hard currency peers – contrary to the consensus expectations at the beginning of the year. We believe there is more to come.

Disclaimer & Important Disclosures

Global Evolution Asset Management A/S (“GEAM”) is incorporated in Denmark and authorized and regulated by the Danish FSA (Finanstilsynet). GEAM DK is located at Buen 11, 2nd Floor, Kolding 6000, Denmark.

GEAM has a United Kingdom branch (“Global Evolution Asset Management A/S (London Branch)”) located at Level 8, 24 Monument Street, London, EC3R 8AJ, United Kingdom. This branch is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority under FCA # 954331. In Canada, while GEAM has no physical place of business, it has filed to claim the international dealer exemption and international adviser exemption in Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec and Saskatchewan.

In the United States, investment advisory services are offered through Global Evolution USA, LLC (‘Global Evolution USA”), a Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) registered investment advisor. Global Evolution USA is located at: 250 Park Avenue, 15th floor, New York, NY. Global Evolution USA is a wholly owned subsidiary of Global Evolution Financial ApS, the holding company of GEAM. Portfolio management and investment advisory services are provided to GE USA clients by GEAM. GEAM is exempt from SEC registration as a “participating affiliate” of Global Evolution USA as that term is used in relief granted by the staff of the SEC allowing U.S. registered investment advisers to use investment advisory resources of non-U.S. investment adviser affiliates subject to the regulatory supervision of the U.S. registered investment adviser. Registration with the SEC does not imply any level of skill or expertise. Prior to making any investment, an investor should read all disclosure and other documents associated with such investment including Global Evolution’s Form ADV which can be found at https://adviserinfo.sec.gov.

In Singapore, Global Evolution Fund Management Singapore Pte. Ltd (“Global Evolution Singapore”) has a Capital Markets Services license issued by the Monetary Authority of Singapore for fund management activities. It is located at Level 39, Marina Bay Financial Centre Tower 2, 10 Marina Boulevard, Singapore 018983.

GEAM, Global Evolution USA, and Global Evolution Singapore, together with their holding companies, Global Evolution Financial Aps and Global Evolution Holding Aps, make up the Global Evolution group affiliates (“Global Evolution”).

Global Evolution, Conning, Inc., Goodwin Capital Advisers, Inc., Conning Investment Products, Inc., a FINRA-registered broker-dealer, Conning Asset Management Limited, Conning Asia Pacific Limited, Octagon Credit Investors, LLC, and Pearlmark Real Estate, L.L.C. and its subsidiaries are all direct or indirect subsidiaries of Conning Holdings Limited (collectively, “Conning”) which is one of the family of companies whose controlling shareholder is Generali Investments Holding S.p.A. (“GIH”) a company headquartered in Italy. Assicurazioni Generali S.p.A. is the ultimate controlling parent of all GIH subsidiaries. Conning has investment centers in Asia, Europe and North America.

Conning, Inc., Conning Investment Products, Inc., Goodwin Capital Advisers, Inc., Octagon Credit Investors, LLC, PREP Investment Advisers, L.L.C. and Global Evolution USA, LLC are registered with the SEC under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 and have noticed other jurisdictions they are conducting securities advisory business when required by law. In any other jurisdictions where they have not provided notice and are not exempt or excluded from those laws, they cannot transact business as an investment adviser and may not be able to respond to individual inquiries if the response could potentially lead to a transaction in securities.

Conning, Inc. is also registered with the National Futures Association. Conning Investment Products, Inc. is also registered with the Ontario Securities Commission. Conning Asset Management Limited is Authorised and regulated by the United Kingdom's Financial Conduct Authority (FCA#189316); Conning Asia Pacific Limited is regulated by Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission for Types 1, 4 and 9 regulated activities; Global Evolution Asset Management A/S is regulated by Finanstilsynet (the Danish FSA) (FSA #8193); Global Evolution Asset Management A/S (London Branch) is regulated by the United Kingdom's Financial Conduct Authority (FCA# 954331); Global Evolution Asset Management A/S, Luxembourg branch, registered with the Luxembourg Company Register as the Luxembourg branch(es) of Global Evolution Asset Management A/S under the reference B287058. It is also registered with the CSSF under the license number S00009438. Conning primarily provides asset management services for third-party assets.

This publication is for informational purposes and is not intended as an offer to purchase any security. Nothing contained in this communication constitutes or forms part of any offer to sell or buy an investment, or any solicitation of such an offer in any jurisdiction in which such offer or solicitation would be unlawful.

All investments entail risk, and you could lose all or a substantial amount of your investment. Past performance is not indicative of future results which may differ materially from past performance. The strategies presented herein invest in foreign securities which involve volatility and political, economic and currency risks and differences in accounting methods. These risks are greater for investments in emerging and frontier markets. Derivatives may involve certain costs and risks such as liquidity, interest rate, market, and credit.

While reasonable care has been taken to ensure that the information herein is factually correct, Global Evolution makes no representation or guarantee as to its accuracy or completeness. The information herein is subject to change without notice. Certain information contained herein has been provided by third party sources which are believed to be reliable, but accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Global Evolution does not guarantee the accuracy of information obtained from third party/other sources.

The information herein is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, accounting, legal or tax advice or investment recommendations.

Legal Disclaimer ©2025 Global Evolution.

This document is copyrighted with all rights reserved. No part of this document may be distributed, reproduced, transcribed, transmitted, stored in an electronic retrieval system, or translated into any language in any form by any means without the prior written permission of Global Evolution, as applicable.

Copyright © 2026 Global Evolution - All rights reserved